‘The Invisible Gorilla’ – Suppose you are asked to

watch a video of two teams of basketball players passing balls around. One team

is dressed in white while the other black. As you are watching, you are tasked

to count the number of passes made by the players in white. Midway through the

video, a man in a gorilla costume walks into the middle of the action, thumps

his chest and slowly walks out the other side. Do you think you would notice

the gorilla? It seems silly to ask this question because the answer is

obviously “yes”.

However, when this experiment was conducted at

Harvard University several years ago, more than half the participants failed to

notice the gorilla. They were so focused on counting the passes that they

completely missed the chest-thumping ape. This study, titled ‘The Invisible

Gorilla’ by psychologists Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons, is one of the

most best-known experiments and it shows that our attention has a capacity

limit – we can only consciously read and process a limited amount of

information at any one time.

At any given moment, facilitators are exposed to

vast amount of sensory information, each vying for his attention. It is humanly

impossible to process every bit of information at the same time due to the

limited mental bandwidth we operate with. Any attempt to consciously stretch

this bandwidth will only result in exhausting our mental state and lowering our

sense of awareness. Try focusing on every object in the space you are at right

now for 60 seconds. What was it like? How did you feel? I bet once the 60

seconds are up, your mind would immediately switch to a ‘break’ mode and go

blank for a few moments.

To make up for this inherent shortcoming,

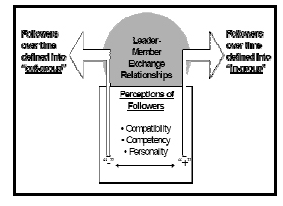

facilitators need to operate with a high level of Situation Awareness (SA). SA

is the ability to recognize, process and comprehend important elements of

information in a given situation. Dr. Mica Endsley, recognized by many as a

pioneer and leader in the study and application of SA, defined it as:

‘…the Perception of the Elements in the

Environment within a Volume of Time and Space, the Comprehension of their

Meaning, and the Projection of their Status in the Near Future.’

In simpler terms, it means making sense of the

current situation and mentally mapping out cause-and-effect relationships.

SA is the radar that operates at the

subconsciously level, constantly scanning the surroundings for abnormalities

and providing updates to our mental model. Like an air-traffic control tower

radar that is continuously feeding the traffic controllers with information, it

identifies aircrafts that are flying too fast or heading towards the wrong

runway while at the same time, provides the controllers with the most updated

view of the air space.

Aside from detecting abnormalities, SA is also

allows facilitators to capture information that are subtle yet significant.

While a facilitator cannot control the amount of sensory elements present, he

can however determine the types of elements to focus on. The more acute his SA

is, the more sensitive he will be to his surroundings and this places him in a

better position to anticipate changes and introduce timely intervention.

High level of SA enables facilitators to:

1) Maintain a high level of safety.

Prevention is better than cure. Having a high SA would lead to a heighten sense

of anticipation. Because facilitators are able to project the plausible

consequences of the current situation, this gives them that extra second to

introduce preventive measures or eliminates threats before they turned into

actual risks.

2) Identify opportunities to enhance the learning

experience.

Seeing things that others do not is one of the hallmark of effective

facilitation. While most would focus on actions that are at the heart of the

activity, seldom would participants reflect on the minor incidents – incidences

that come as quickly as they go. Part of SA is about being sensitive to these

minor, and to many, insignificant incidences. Insightful learning, the kind

that people do not recognize at first but seems so apparent when pointed out,

are created when facilitators are able to spot these opportunities and create

meaning off them.

3) Adjust delivery style.

Another hallmark of effective facilitation is the facilitator’s ability to

adjust his delivery style. Once in a while, concerned and discomforted

participants will question the facilitators’ style of delivery, but these are

exceptions to the rule. In the Asian context, out of respect to the facilitators,

most participants tend to keep to themselves and go with the flow. Not knowing

what participants are truly feeling is a major stumbling block because the

facilitator might be thinking he is doing the ‘right’ thing and would continue

doing so.

By the time participants surface their concerns,

it might already be too late because the damage is done. Two common cases are;

1) When the facilitator is being too strict with the rules. 2) When the

facilitator uses languages that some participants are uncomfortable with. For

example, jokes on sexual orientation might not fit well with participants who

are strong believer of the LGBT social movement.

However, when facilitators are able to detect

signs of discomfort, or feel a sense of passive aggressiveness from the

participants early, they can make the necessary adjustments to their delivery

before more damages are done.

4) Making better decisions, spontaneously.

Facilitators make spontaneous decisions all the time because no matter how well

the programmes are designed and planned, it is not possible to factor in every

possible variable. Seasoned facilitators have countless tales of curveball

anecdotes. In order to make better and more informed snap decisions to respond

to changing and emerging patterns, facilitators need to stay two steps ahead of

the situation. For example, knowing what to do the moment grey clouds are

spotted or how to adjust the programme in the event of a delay in catering

services.

Here is the good news – SA is not an inborn

ability that is bestowed to a lucky few. SA is an ability that facilitators can

work on and be better at, it is a sense that can be trained, like a highly

trained nurse who can read the faintest of pulse or a skilled wine sommelier

who can give a full description with a single sip. Increased exposure and field

time is widely acknowledged as key pillars in building up one’s SA. In a series

of studies conducted by researcher Gary Klein on how experts in various fields

make spontaneous decision in urgent situations, he found out that these

individuals are able to tap on the wealth of experiences they have amassed over

years of practice and understanding. One of the better-known case studies is

about a seasoned fire fighter, who made the decision to pull his team out of a

burning building moment before it collapsed, though there were no obvious signs

of any structural damage. In an interview later, the fire fighter said he felt

a hunch and something in his mind told him that the building was going to give

way soon, and that made him pulled his team out.

Although experience is key to the development of

SA, paradoxically, experience is also SA biggest enemy because the more

experienced a facilitator is, the more likely he will fall into a routine

mindset, let his senses down and allow complacency to sip in. This transition

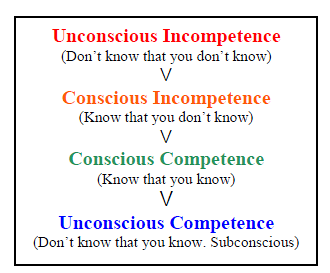

from experience to complacency is best explained through the “conscious

competence” framework:

1. Unconscious incompetence

A rookie facilitator does not recognize SA as an important feature and might

deny the usefulness of the skill. The facilitator must recognize his own

incompetence and the value of SA before moving on to the next stage.

2. Conscious incompetence

The training facilitator now knows what SA is and acknowledges that it is a

skill he lacks. He makes effort to work on his SA.

3. Conscious competence

The trained facilitator now understands how to apply SA, but he needs to

concentrate and think in order to use it effectively. Without thorough

cognitive effort, his SA might not be as reliable. It is only through constant

practice would his SA move to the next stage.

4. Unconscious competence

The seasoned facilitator has had so much practice that SA has entered the

unconscious part of the brain and it has become “second nature”. As a result,

he no longer needs to consciously think about applying SA.

5. Complacency

Once SA operates at the subconscious level, the seasoned facilitator might

missed the natural ‘check and balance’ system that comes with conscious

thinking, thus, opening up opportunities for the occasional lapse in attention.

Inexperience facilitator requires field time and practice to sharpen their SA,

seasoned practitioners too need to remind themselves on the trappings of

complacency. Below is a list of techniques rookie facilitator can work on to

improve their SA and seasoned practitioners can adopt to guard against

complacency.

1. Active involvement – SA is not a passive

process, it does not just come on to the facilitator. For SA to function

effectively, one has to play an active role and be with the situation. This

means the facilitator has to be mentally present, consciously making sense of

the events that are taking place around him. Active involvement requires the

facilitator to stay engage with the process and be as involved as the

participants through the experience.

2. Setting goals – Professor Kip Smith and Dr.

Peter Hancock, prominently researchers in the field of aviation and human

behavior in dynamic situations, defined SA as ‘adaptive, externally directed

consciousnesses. They see SA as an intentional behavior that is directed

towards the goal. In other words, we assess what we set out to assess. Our SA

is most sensitive towards the objectives we set because our focus is primarily

on them. Setting goals will help funnel our attention towards key areas.

Clearly defined goals serve as both guide and reminder to the facilitator on

what to look out for. Because human’s attention is limited and easily

distracted, the way in which our attention is deployed will determine what is

read. Before an activity commences, facilitators should be clear on where to

focus their attention on, for example, to capture specific learning

opportunities and/or to mitigate risk at a precise point. These points for

attention could also be a specific time, juncture, person, situation, reaction

or conversation.

3. Delegate responsibilities to co-facilitators or

participants – There will be occasions where there are simply too many things

taking place at the same time. In such instances, a facilitator can either

split the area of focus with his co-facilitator (one concentrate on safety

while another concentrate on learning moments) or delegate secondary roles to

the participants, such as ‘Safety Officer’.

4. Expose to a variety of experiences – Facilitators who limit themselves to a

small number of programme types will develop very sharp sense of SA but only in

environments they are extremely familiar with. Conversely, facilitators who

expose themselves to a wider range of experiences will develop wellrounded SA

that can be applied effectively across various situations. For experience

facilitators, exposing themselves to fresh challenges is one of the best way to

guard against complacency because it reminds them that learning is an on-going

process and that no facilitator can ever claim to have enough SA.

SA serves two fundamental purposes. Firstly, it

enables facilitators to maintain a high level of safety. No facilitator ever

plans for things to go wrong. The reality is, no matter how well the programmes

are designed and how clear our instructions to the participations are,

accidents are unavoidable. Accidences are after all, a matter of statistics. It

is at these points where the facilitator’s foresight, speed of reaction and

judgment makes all the differences and SA is central to this process. Secondly,

SA supports a higher standard of learning. It is a facilitator’s ability to

spot learning moments that are otherwise oblivious to everyone, and make sense

of it that would create the most value to the learning process. It is here

where facilitators can stimulate the deepest reflection amongst the team because

it examines the underlying forces that drove the participants’ behaviors.

Behaviors so instinctive that is invisible to most, but so apparent once they

are pointer out. Just like the gorilla in the video. “people will focus on

procedures and not notice anything that isn’t just part of the procedures”

― Daniel Simons, author of ‘The Invisible Gorilla’